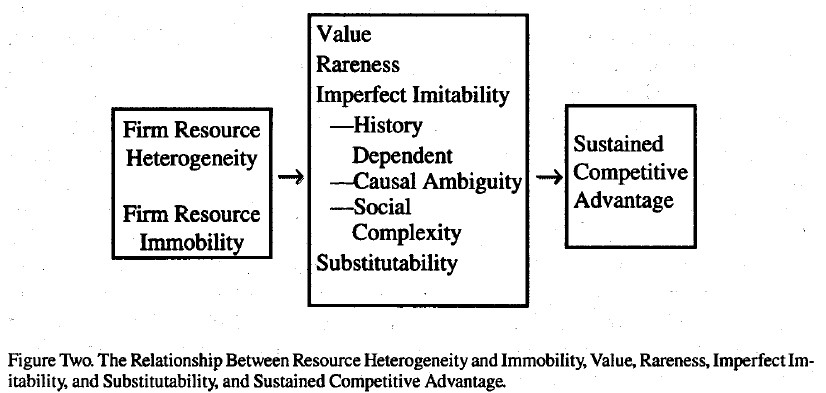

We review the main contents of the VRIN model or VRIO framework, developed from the research of Barney, published in Journal of Management in 1991. This framework focuses on the attributes of resources that allow firm generating its sustainable competitive advantage. Four attributes of such resources include value, rareness, imitability, and non-substitutability or so-called question of “organization”.

Defining Key Concepts

In the VRIO framework, firm resources are defined as including all assets, capabilities, organizational processes, firm attributes, information, knowledge, etc., controlled by a firm, that enable the firm to conceive of and implement strategies, that improve its efficiency and effectiveness. In the language of traditional strategic analysis, firm resources are strengths that firms can use to conceive of and implement their strategies.

Also, by definition, a firm is said to have a competitive advantage, when it is implementing a value creating strategy, not simultaneously being implemented by any current or potential competitors. A firm is said to have a sustainable competitive advantage, when it is implementing a value creating strategy, not simultaneously being implemented by any current or potential competitors; and when these other firms are unable to duplicate the benefits of this strategy.

The VRIN model

According to the resource-based view, in order to have potential of sustainable competitive advantages, a firm resource must have four attributes, that constitute the VRIN (Value – Rareness – Immitablility – Non-substitutability) model.

Valuable Resources

Firstly, it must be valuable. “Resources are valuable, when they enable a firm to conceive of or implement strategies, that improve its efficiency and effectiveness” (Barney, 1991, p. 106). “Firm attributes may have the other characteristics, that could qualify them as sources of competitive advantage (eg., rareness, inimitability, non-substitutability), but these attributes only become resources, when they exploit opportunities or neutralize threats in a firm’s environment” (Barney, 1991, p. 106).

Rare Resources

Secondly, resources must be rare among a firm’s current and potential competition. “A firm enjoys a competitive advantage, when it is implementing a value-creating strategy not simultaneously implemented by large numbers of other firms” (Barney, 1991, p. 106). “If this particular bundle of firm resources is not rare, then large numbers of firms will be able to conceive of and implement the strategies in question, and these strategies will not be a source of competitive advantage, even though the resources in question may be valuable” (Barney, 1991, p. 106).

So, “the observation, that valuable and rare organizational resources can be a source of competitive advantage, is another way of describing first-mover advantages accruing to firms with resource advantages” (Barney, 1991, p. 107).

Imperfectly Imitable Resources

“However, valuable and rare organizational resources can only be sources of sustained competitive advantage, if firms that do not possess these resources cannot obtain them” (Barney, 1991, p. 107). So, thirdly, “firm resources can be imperfectly imitable for one or a combination of three reasons: (a) the ability of a firm to obtain a resource is dependent upon unique historical conditions, (b) the link between the resources possessed by a firm and a firm’s sustained competitive advantage is causally ambiguous, or (c) the resource generating a firm’s advantage is socially complex” (Barney, 1991, p. 107).

The unique historical conditions or path dependency mean that, the ability of a firm to acquire and exploit some resources depends upon their place in time and space; so in history passes. “If a firm obtains valuable and rare resources because of its unique path through history, it will be able to exploit those resources in implementing value-creating strategies, that cannot be duplicated by other firms” (Barney, 1991, p. 108); for example: their unique location, particulars scientists, unique and valuable organizational culture emerged in the early stages of a firm’s history.

The causal ambiguity concerns the link between the resources possessed by a firm and a firm’s sustained competitive advantage, that is causally ambiguous. “Under conditions of causal ambiguity, it is not clear that, the resources, that can be described, are the same resources that generate a sustained competitive advantage, or whether that advantage reflects some other non-described firm resource” (Barney, 1991, p. 109). “The resources controlled by a firm are very complex and interdependent. Often, they are implicit, taken for granted by managers, rather than being subject to explicit analysis” (Barney, 1991, p. 110), so not simply by hiring some managers.

Also, the resource generating a firm’s advantage is socially complex, beyond the ability of firms to systematically manage and influence, for example, the interpersonal relations among managers in a firm, a firm’s culture, a firm’s reputation among suppliers and customers. “To the extent that socially complex firm resources are not subject to such direct management of the firm, these resources are imperfectly imitable” (Barney, 1991, p. 110). In particular, we emphasize that the complex physical technology is not included in this category of sources of imperfectly imitable, because the other firm can buy it.

Non-Substitutability

“The last requirement for a firm resource to be a source of sustained competitive advantage is that, there must be no strategically equivalent valuable resources that are themselves either not rare or imitable. Two valuable firm resources are strategically equivalent, when they each can be exploited separately to implement the same strategies. Suppose that one of these valuable firm resources is rare and imperfectly imitable, but the other is not. Firms with this first resource will be able to conceive of and implement certain strategies. If there were no strategically equivalent firm resources, these strategies would generate a sustained competitive advantage, because the resources used to conceive and implement them are valuable, rare, and imperfectly imitable. However, that there are strategically equivalent resources suggests that other current or potentially competing firms can implement the same strategies, but in a different way, using different resources. If these alternative resources are either not rare or imitable, then numerous firms will be able to conceive of and implement the strategies in question, and those strategies will not generate a sustained competitive advantage. This will be the case even though one approach to implementing these strategies exploits valuable, rare, and imperfectly imitable firm resources.

Substitutability can take at least two forms. First, though it may not be possible for a firm to imitate another firm’s resources exactly, it may be able to substitute a similar resource that enables it to conceive of and implement the same strategies. For example, a firm seeking to duplicate the competitive advantages of another firm by imitating that other firm’s high-quality top management team will often be unable to copy that team exactly. However, it may be possible for this firm to develop its own unique top management team. Though these two teams will be different, then a high-quality top management team is not a source of sustained competitive advantage, even though a particular management team of a particular firm is valuable, rare and imperfectly imitable.

Second, very different firm resources can also be strategic substitutes. For example, managers in one firm may have a very clear vision of the future of their company because of a charismatic leader in their firm. Managers in competing firms may also have a very clear vision of the future of their companies, but this common vision may reflect these firms’ systematic, company-wide strategic planning process. From the point of view of managers having a clear vision of the future of their company, the firm resource of a charismatic leader and the firm resource of a formal planning system may be strategically equivalent, and thus substitutes for one another. If large numbers of competing firms have a formal planning system that generates this common vision, or if such a formal planning is highly imitable; then firms with such a vision derived from a charismatic leader will not have a sustained competitive advantage, even though the firm resource of a charismatic leader is probably rare and imperfectly imitable.

Of course, the strategic substitutability of firm resources is always a matter of degree. It is the case, however, that substitute firm resources need not have exactly the same implications for an organization in order for those resources to be equivalent from the point of view of the strategies that firms can conceive of and implement. If enough firms have these valuable substitute resources, for example they are not rare; or if enough firms can acquire them, for example they are imitable; then none of these firms, including firms whose resources are being substituted for, can expect to obtain a sustained competitive advantage” (Barney, 1991, p. 111-112).

The VRIN Model evolved to VRIO framework

The VRIN model evolved then to VRIO framework by giving us a complete framework. The change of the last letter of the acronym refers to the so-called question of “organization”, which is the ability of the firm to exploit the resource or capability. In fact, the business must also be ready and able to utilize the resource to capitalize on its value. A resource that meets each of these four criteria can bring about competitive advantage to the business. The VRIN model or VRIO framework is particularly useful for assessing and analyzing a firm’s internal resources and its potential for applying these resources to achieve competitive advantage.

Applying the Framework

This VRIN model or VRIO framework, summarized in this Figure, can be applied in analyzing the potential of a broad range of firm resources, to be sources of sustainable competitive advantage. Three brief examples of how this framework might be applied are presented below.

Source: Barney (1991)

Firstly, it seems reasonable to expect that the informal strategic planning systems, but not the formal ones, are likely by themselves to be a source of sustainable competitive advantage. Because the informal processes are often socially complex, and also likely to be imperfectly imitable. In contrast, any firm interested in engaging in formal planning can certainly learn how to do so, and thus formal planning seems likely to be highly imitable, so not likely to be a source of sustainable competitive advantage.

Secondly, an information processing system, that is deeply embedded in a firm’s informal and formal management decision-making process, may hold the potential of sustainable competitive advantage. This is also a socially complex system, and thus will probably be imperfectly imitable. So, an embedded information-processing system may be a source of sustainable competitive advantage, even if a close substitute for such a processing system exists.

Thirdly, positive reputations of firms among customers and suppliers have also been cited as sources of competitive advantage in the literature. In general, the development of a positive reputation usually depends upon specific, difficult-to-duplicate historical settings. In addition, positive firm reputations can be thought of as informal social relations between firms and key stakeholders. Such informal relations are likely to be socially complex, and thus imperfectly imitable. So, these make the positive reputations are likely to be a source of sustainable competitive advantage of the firm.

Source: Barney Jay (1991), “Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage”, Journal of Management, 17 (March), p. 99-120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108