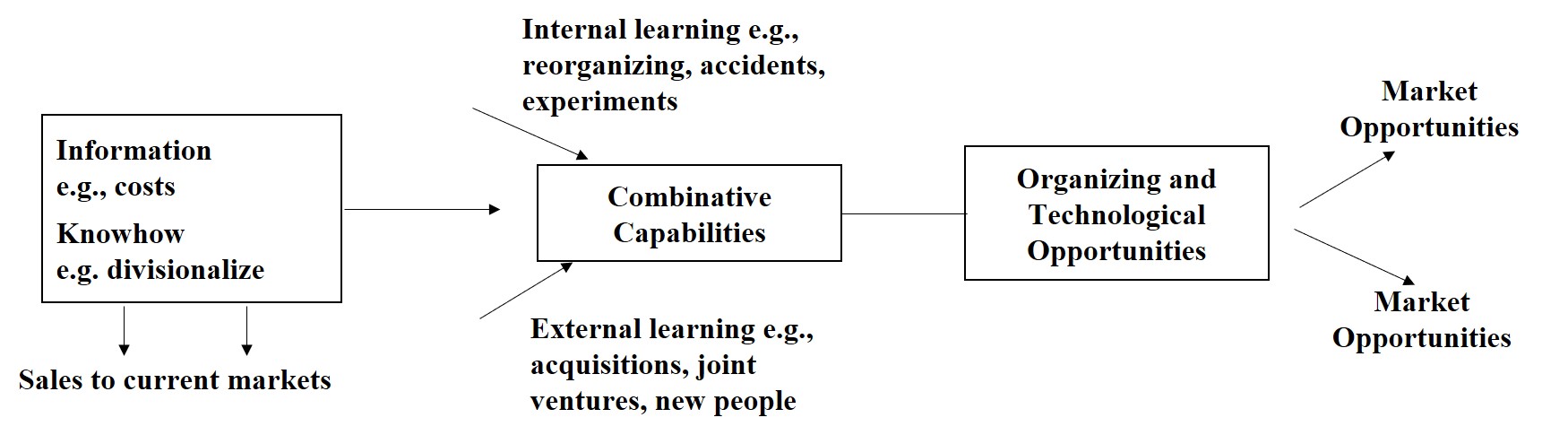

This article present the model of growth of knowledge of the firm, that is developed by Kogut and Zander (1992) in their famous article published in 1992 in Organization Science. This model explains what is knowledge, and how it develop within the firm. In the knowledge-based view, the central competitive dimension of what firms know how to do, is to create and transfer knowledge efficiently within an organizational context. For understanding this process, Kogut and Zander (1992) developed a model of growth of knowledge of the firm, in which, they categorize organizational knowledge into information and know-how; that are the basis of the growth of knowledge of the firm.

Information and Know-How

We begin by analyzing the knowledge of the firm by distinguishing between information regarding prices, and the know-how, say, to divisionalize. By information, Kogut and Zander (1992) “mean knowledge which can be transmitted without loss of integrity, once the syntactical rules required for deciphering it are known. Information includes facts, axiomatic propositions, and symbols”. “Know-how is the accumulated practical skill or expertise, that allows one to do something smoothly and efficiently”. “Knowledge as information implies knowing what something means. Know-how is, as the compound words state, a description of knowing how to do something”. “The information is contained in the original listing of ingredients, but the know-how is only imperfectly represented in the description”.

Figure 1: Growth of Knowledge of the Firm

Source: Kogut and Zander (1992, p.385)

This distinction of information and know-how corresponds closely to that used in artificial intelligence of declarative and procedural knowledge. “Declarative knowledge consists of a statement that provides a state description, such as the information that inventory is equal to 100 books. Procedural knowledge consists of statements that describe a process, such as a method by which inventory is minimized”. “Know-how, like procedural knowledge, is a description of what defines current practice inside a firm. These practices may consist of how to organize factories, set transfer prices, or establish divisional and functional lines of authority and account-ability”. “The know-how is the understanding of how to organize a firm along these formal and informal lines. It is in the regularity of the structuring of work, and of the interactions of employees conforming to explicit or implicit recipes, that one finds the content of the firm’s know-how”.

The Inertness of Knowledge

There is a need to go beyond the classification of information and know-how, and consider why knowledge is not easily transmitted and replicated. The transferability and imitability of a firm’s knowledge, whether it is in the form of information or know-how, are influenced by several characteristics.

“Consider the two dimensions of codifiability and complexity of knowledge. Codifiability refers to the ability of the firm to structure knowledge into a set of identifiable rules and relationships, that can be easily communicated. Coded knowledge is alienable from the individual who wrote the code. Not all kinds of knowledge are amenable to codification”. Complexity, from a computer science perspective, “can be defined as the number of operations required to solve a task”.

“Codifiability and complexity are related, though not identical. It is obvious that: the number of parameters required to define a production system is dependent upon the choice of mathematical approaches or programming languages. For a particular code, the costs of transferring a technology will vary with its complexity. A change of code changes the degree of complexity”.

So, Kogut and Zander (1992) underline the presumption that: “the knowledge of the firm must be understood as socially constructed, or more simply stated, as resting in the organizing of human resources”. And “the capabilities of the firm are argued to rest in the organizing principles, by which, relationships among individuals, within and between groups and among organizations, are structured”. “The issue of the organizing principles, that underline the creation, replication and imitation of technology, opens a window on understanding the capabilities of the firm as a set of “inert” resources, that are difficult to imitate and redeploy”.

Combinative Capabilities of the firm and The Paradox of Replication

For explaining how firm learn and develop their organizational knowledge, Kogut and Zander (1992) introduce the concept of combinative capability, that means “the intersection of the capability of the firm to exploit its knowledge and the unexplored potential of the technology”. They develop a dynamic perspective by suggesting that: “Creating new knowledge does not occur in abstraction from current abilities. Rather, new learning such as innovations, are products of a firm’s combinative capabilities to generate new applications from existing knowledge”. In other words, firms learn new skills by recombining their current capabilities. “Knowledge advances by re-combinations, because a firm’s capabilities cannot be separated from how it is currently organized”. As Schumpeter argued that: innovations are new combinations of existing knowledge and incremental learning.

“As widely recognized, firms learn in areas closely related to their existing practice. As the firm moves away from its knowledge base, its probability of success converges to that for a start-up operation”. “The abstract explanation for this claim is that the growth of knowledge is experiential, that is, it is the product of localized search as guided by a stable set of heuristics, or in our terminology, know-how and information. It is this local search that generates a condition commonly called “path dependence,” that is the tendency for what a firm is currently doing to persist in the future”. Because new ways of cooperating cannot be easily acquired, growth occurs by building on the social relationships that currently exist in a firm. What a firm has done before tends to predict what it can do in the future”.

So, the firm serves more than mechanisms by which initial social knowledge is transferred, but also by which new knowledge, or learning, is created through its “combinative capability”. This capability is grounded “as localized learning to path dependence, by developing a micro-behavioral foundation of social knowledge, while also stipulating the effects of the degree of environmental selection on the evolution of this knowledge”.

For a firm to grow, it must develop organizing principles and a widely-held and shared code, by which, to orchestrate large numbers of people and potential varied functions. The speed of replication of knowledge determines the rate of growth; control over its diffusion deters competitive erosion of the market position”.

And “there is an important implication for the growth of the firm, in the transformation of technical knowledge into a code understood by a wide set of users”. “Because personal and small group knowledge is expensive to re-create, firms may desire to codify and simplify such knowledge as to be accessible to the wider organization, as well as to external users”.

The problems of the growth of the firm are directly related to the issues of technology transfer and imitation. Once organizing principles replace individual skills of the entrepreneur, they serve as organizational instructions for future growth. From this perspective, Technology transfer is the replication of existing activities. The goal of the firm is to reduce the costs of this transfer, while preserving the quality and value of the technology. Whereas the advantages of reducing the costs of intra, or inter-firm technology transfer encourage codification of knowledge, such codification runs the risk of encouraging imitation from competitors. It is in this paradox that the firm faces a fundamental dilemma.

In fact, “Imitation differs from technology transfer in a fundamental sense. Whereas technology transfer is concerned with adapting the technology to the least capable user, the threat of imitation is posed by the most capable competitors”. On the market, when absent of the entry-deterring benefits such as these ones of reputation among consumers, patent protection, or the exercise of monopoly restrictions; competition switches from traditional elements of market structure, to the comparative capabilities of firms to replicate and generate new knowledge. “The nature of this competition is frequently characterized as a race between an innovator, and the ability of the imitating firm either to reverse engineer, and to decode the substantive technology. The growth of the firm is determined by a combination of the speed of technology transfer, and of the imitative efforts of rivals”.

Selection Environment

Up to now, Kogut and Zander (1992) have explained the role of organizing principles to facilitate the transfer of technology, and ideas within the organization of the firm. The distinction between the ability to produce a product, and the capability to generate, is fundamental to broadening the perspective to the competitive conditions of imitation.

“Short-term competitive pressures can draw from the investments required to build new capabilities. The direct effect of selection is on the acceptance and rejection of new products, but indirectly, it is operating to reward, or to penalize the economic merits of the underlying stock of knowledge. Knowledge, no matter how resistant to imitation, is of little value if it results in products that do not correspond competitively to consumers’ wants. Selection on product types acts to develop and retard the capabilities of firms”.

“The ability to indulge in a forward-looking development of knowledge is strongly contingent on the selection environment. Long-term survival involves a complex tradeoff between current profitability and investing in future capability. Future capabilities are of little value if the firm does not survive”. So, an important question is the critical balancing between short-term survival and the long-term development of capabilities. A too strong reliance on current profitability can deflect from the wider development of capabilities. Also, “a too rigid competitive environment, especially in the early years of a firm’s development, may impede subsequent performance by retarding a firm’s ability to invest in new learning”. “By their ability to buffer internal ventures from an immediate market test, organizations have the possibility to create new capabilities by a process of trial-and-error learning”.

So, we have presented to you the model of growth of knowledge of the firm, that explains how organizational knowledge occur and develop within the firm.

Source: Kogut Bruce, Zander Udo (1992), “Knowledge of the Firm, Combinative Capabilities, and the Replication of Technology”, Organization Science, Vol. 3, No. 3, Pages 301-441. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.3.3.383

25 Jan 2022